C#’s finalizer/destructor trap

Let’s talk about C#’s finalizers (also called destructors in C#) and how a common mistake when using them might lead to unwanted behavior, especially in applications made with the Unity engine.

Finalizers

A finalizer is a method that is called whenever an instance of a class is being garbage-collected. It is used for cleanup, commonly to release resources. The code below contains an example class for a music player, where its destructor closes an open file. Note that finalizers always start with a tilde and can’t have any parameters.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

public class MusicPlayer

{

private FileStream _file;

public void Play(string filePath)

{

_file = File.Open(filePath, FileMode.Open);

// ...

}

~MusicPlayer()

{

if (_file != null)

_file.Close();

}

}

Disclaimer: even though destructors and finalizers are two different things, C#’s spec treats them as the same. If you’re acquainted with both definitions, the C#’s mechanism discussed in this article is actually a finalizer. Also, if you come from a C++ background, even though C#’s syntax for finalizers resembles C++’s syntax, keep in mind that they’re not the same. C++ destructors are called explicitly (and deterministically) by the user whereas C#’s finalizers are called implicitly (and nondeterministically) by the garbage collector.

A quick intro to Unity’s MonoBehaviour

The Unity engine provides a handy base class (MonoBehaviour) that contains common behavior often needed for game development. Among other things, it contain event methods that are automatically called by the engine under given scenarios. These event methods are guaranteed to be called under the right circumstances and therefore developers can rely on them. Some of these methods are called when an object is created and when it’s destroyed, analogous to constructors and finalizers (which should not exist for MonoBehaviours). For example, the Awake methods is called when an object is created and the OnDestroy method is called when it’s destroyed.

Common practice

It is common practice to use Awake and OnDestroy to subscribe and unsubscribe to events, respectively. The code below shows an example.

The ExampleButton behavior contains only an event, for example purposes:

1

2

3

4

public class ExampleButton : MonoBehaviour

{

public event Action OnClick;

}

The MyBehaviour behavior subscribes to _button‘s OnClick event when it’s created and unsubscribes to the same event when it’s destroyed.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

public class MyBehaviour : MonoBehaviour

{

[SerializeField] private ExampleButton _button;

private void Awake()

{

_button.OnClick += Foo;

}

private void OnDestroy()

{

_button.OnClick -= Foo;

}

private void Foo()

{

// ...

}

}

The code above works as expected and both initialization and cleanup execute as expected.

The naive thought

At some point during development, we introduce a regular, non-MonoBehaviour class called ExampleClass. Unlike MonoBehaviours, it can’t rely on event methods like Awake for initialization. As an alternative, we normally use the class’ constructor. Analogously, ExampleClass can’t rely on event methods like OnDestroy for cleanup. As an alternative, we use its finalizer.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

public class ExampleClass

{

private string _name;

private ExampleButton _button;

public ExampleClass(string name, ExampleButton button)

{

_name = name;

_button = button;

_button.OnClick += Bar;

}

~ExampleClass()

{

Debug.Log($"Calling {_name} destructor.");

_button.OnClick -= Bar;

}

private void Bar()

{

// ...

Debug.Log("Bar");

}

private static void Something()

{

Debug.Log("Something");

}

}

Let’s define ExampleBehaviour, a MonoBehaviour that contains an ExampleButton and an ExampleClass. On its Awake method, the _objectfield (of type ExampleClass) is initialized.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

public class ExampleBehaviour : MonoBehaviour

{

[SerializeField] private ExampleButton _button;

private ExampleClass _object;

private void Awake()

{

_object = new ExampleClass("Foo", _button);

}

}

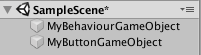

A new Unity scene is created and only 2 objects are added to it: one containing an ExampleButton (called MyButtonGameObject) and one containing an ExampleBehaviour (called MyBehaviourGameObject). Whenever the scene is played, MyBehaviourGameObject’s Awake method is invoked and the _objectvariable is assigned, as expected. Inside ExampleClass constructor, the event subscription is executed, as expected. Nothing unusual so far.

Then, because of some design decision, the MyBehaviourGameObject object is destroyed along the application lifetime. We realize that we might have to do some cleanup because _object should unsubscribe from _button‘s OnClickevent. But then we come to the conclusion that it actually should be alright and that no additional cleanup should be necessary. Whenever MyBehaviourGameObject gets destroyed, the garbage collector will collect its ExampleBehaviour script. Since _object only belongs to MyBehaviourGameObject, it should be collected as well, which should trigger its finalizer and unsubscribe from the events.

The trap

Later during development, we notice some weird behavior whenever the user clicks on MyButtonGameObject: there’s ExampleClass behavior still being executed. But at that point of the execution, there should be no activeExampleClass in the scene because MyBehaviourGameObject was destroyed! After checking the call stack, we find out that Bar is being called by ExampleButton‘s OnClick event. But wait a second, something is wrong. ExampleClass‘s finalizer was responsible for event unsubscription. What happened? After some more debugging, you finally find out that the object’s finalizer doesn’t ever get called. But why isn’t the finalizer being called at all?

Maybe the garbage collector is not running, for whatever reason. Let’s try to force collection using a simple script.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

public class ManualGarbageCollector : MonoBehaviour

{

private void Update()

{

if (Input.GetKeyDown(KeyCode.C))

GC.Collect();

}

}

For testing purposes, I manually delete MyBehaviourGameObject and press the C key. The finalizer is still not executing. What is going on? Is the garbage collector broken? MyBehaviourGameObject was destroyed and _object should be collected, which should trigger the event unsubscription.

To answer those question, we need to understand how C#’s garbage collector works. First, no, it’s not broken at all. In fact, it’s doing exactly what it’s told to. It’s our minds that forgot what we were doing. An object will only get collected whenever there are no references to it. None at all. Zero. If there’s one, even if really hidden, forgotten reference to an object, it will not get collected by the garbage collector. It’s as simple as that. But it still doesn’t make sense. The only reference to _object was inside ExampleBehaviour, right?

Wrong.

We forgot about the one reference we were trying to get rid of: the one inside ExampleButton‘s OnClick event. But wait a second, we didn’t store a reference to _object in that event, we just stored a reference to a method, right?

Again, wrong. Although it looks like we’re subscribing to a method, we need to keep in mind that it’s an instance method. It belongs to an instance of a class, a.k.a. an object. Under the hood, that method’s reference consists – among other things – of a reference to the method in memory and a reference to the instance the methods should be called on. If you ever programmed in Python, think of how the first argument of an instance method is self. As a consequence, an event subscription to an instance method will keep a reference to the instance itself. Therefore, it will stop the object of being collected by the garbage collector.

We can show show that _object‘s reference is, in fact, being kept by MyButtonGameObject by destroying the latter. Once destroyed, the garbage collector will collect ExampleButton‘s memory and later, _object.

If Bar was a static method, this wouldn’t happen because references to static methods don’t include a reference to an object. Consequently, _object‘s reference count would drop to 0 and it would be eventually collected by the garbage collector.

The solution

Thankfully, there is an easy solution for that: create a cleanup method and explicitly call it whenever necessary. On this article’s example, the perfect candidate would be ExampleBehaviour‘s OnDestroy method.

On ExampleClass:

1

2

3

4

public void Cleanup()

{

_button.OnClick -= Bar;

}

On ExampleBehaviour:

1

2

3

4

private void OnDestroy()

{

_object.Cleanup();

}

This fix not only will guarantee that events get unsubscribed but it will also – ironically – remove the last references to _object, which allows its (now obsolete) finalizer to be called.

The bonus trap

There’s another trap regarding finalizers that is not related to the one described above. Finalizers are called by the garbage collector, which runs on a separate thread than Unity’s main thread. As a consequence, two problems might come up.

First – as usual – Unity engine code can not be called from a separate thread. Calling something as simple as _foo.gameObject will throw a UnityEngine.UnityException with the message “get_gameObject can only be called from the main thread“.

Second, Unity will not catch and log exceptions running on separate threads. Therefore, any exceptions thrown inside finalizers (like the one described above) or in any separate thread might fly under the radar and never get acknowledged by the developers. There are two possible fixes for this problem. One is the obvious: catch the exceptions inside the thread itself. Another one can be used for user-defined threads (and thus is not applicable to GC threads): use Task instead of Thread to start a new thread with exception handling support.

Conclusion

Whenever using C# finalizers, keep in mind that they will only get called when no references to their respective objects are left, including references to instance methods. Therefore, using finalizers to unsubscribe from events and to remove delegate references might lead to unwanted behavior. As an alternative, create a cleanup method and explicitly call it whenever necessary.

As a good practice, try to use finalizers for what they are good for: freeing resources. For other usages, don’t rely on them and explicitly invoke cleanup methods. Some even say that pure finalizers should avoided and the disposable pattern should be used instead.

That’s all for today. As usual, feel free to leave a comment with corrections, questions, criticism or compliments. See you next time!

Comments

Thanks mate, I appreciate the quality content

You’re welcome! I’m glad you enjoyed it.